A couple of days before Guy Fawkes night in 1831, 10 year old John King and his 11 year old sister Martha were hanging out the washing to help their invalided mother at their home in Crabtree Road, at the northern end of Bethnal Green. Looking across the road to the Bird Cage public house in Nova Scotia Gardens, they noticed a boy, slightly older than themselves, who waved before uttering something in a foreign language that the two children couldn’t understand. It was the last time they were to see 14 year old Italian Carlo Ferrier alive – The London Burkers had struck again…

Nova Scotia Gardens was an area of the East End, just to the north-east of St Leonard’s Church in Shoreditch that had been extensively used to extract clay for brick making. Once the clay field had been exhausted the area begun to be filled in with ‘leystall’ waste, quite literally excrement. Some dwellings, mainly small cottages, were built in the area, but were largely undesirable as, being built on the lower ground of the clay pits, they were prone to flooding. The properties were to attract the lowest, most desperate kind of tenants…

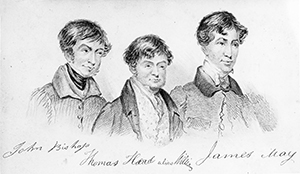

The London Burkers – Bishop, Williams and May

Four such individuals were Thomas Williams, John Bishop, a Covent Garden porter called Michael Shields and an unemployed butcher called James May.

In the 18th century, demand for anatomical cadavers was high – around 500 were needed each year to meet demands, and the bodies of convicted and hanged criminals met that requirement. However, whilst hundreds were executed during the 18th century, the mid 19th century saw just 55 being hanged each year. Demand clearly outstripped supply and it was into this lucrative market that Williams, Bishop, Shields and May were drawn.

Modelling their activities on the notorious Burke and Hare, two grave robbers in Scotland, these ‘London Burkers’, bodysnatchers or so called ‘resurrectionists’ would dig up and sell fresh cadavers to the anatomists and surgeons at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, St Thomas’ Hospital and Kings College. Bishop, in a subsequent confession, admitted to stealing between 500 and 1000 bodies in this manner over a twelve year period. However, the Burkers needed even more bodies…

On Saturday 5th November 1831, May and Bishop delivered the suspiciously fresh body of a young boy to William Hill, the porter of the dissecting room at King’s College, Somerset House and demanded twelve guineas for the corpse. May and Bishop tipped the corpse out of a hamper and pointed out to a startled Hill how fresh the body was. When questioned how the boy had died, both May and Bishop claimed they didn’t know, and that it was ‘no business of theirs’. Hill called Richard Partridge, the Demonstrator of Anatomy at the college to examine to body, and he alerted the Professor of Anatomy, Herbert Mayo. Mayo immediately called the police and the resurrectionists were duly arrested and remanded in custody…

The London Burkers in the Dock

Two weeks later, Joseph Sadler, a Superintendent with F division of the Metropolitan Police searched the cottage at Nova Scotia Gardens. He found numerous items of clothing in the gardens and in a well at the property, all of which suggested multiple murders. Williams and Shields were duly arrested and placed with May and Bishop. Upon questioning, it became apparent that the men had been complicit in the murder of a woman, Frances Pigburn and another boy named Cunningham who they had found sleeping rough in a pig market in Smithfield. Both had been taken back to Nova Scotia Gardens, drugged with a mixture of warm beer, sugar, rum and laudanum. They were then hung upside down and drowned in the well at the property.

The men were tried collectively, but the testimony of Bishop and Williams cleared the remaining two members of the gang, who appeared to have been mere ‘delivery men’ in the affair. Bishop, aged 33 and Williams, aged 26 were found guilty and both were hanged at Newgate on 5th December 1831 in front of a crowd of 30,000 onlookers. Their bodies were subsequently cut down and dispatched to anatomical establishments – for dissection…