Just before 7pm on the evening of Friday the 19 January 1917, with Britain firmly in the grip of WWI, the people of Silvertown were settling down to their evening meals. Suddenly, the winter’s night lit up and the howl and roar of an enormous explosion rent the East London sky apart. Debris was strewn across much of London: a gasholder across the river in Greenwich exploded, igniting over 7 million cubic feet of gas, and windows were reportedly blown out of the Savoy Hotel on the Strand. Red hot lumps of rubble fell from the sky and began to cause numerous fires in the surrounding areas. What on earth had happened?

The Silvertown explosion wrecked the docks

Silvertown is an area of London just to the south of the Royal Victoria Docks, on the far eastern fringes of the East End. It has long been an area of industry and was named after Samuel Winkworth Silver who established a factory there in the 1850’s and who went on to make some of the first of Alexander Graham Bell’s telephones there in the 1880’s.

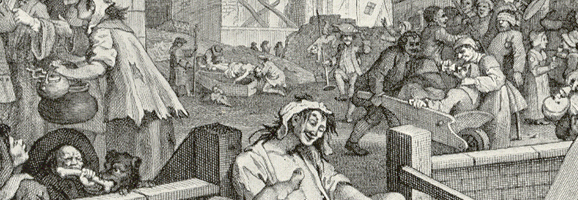

As Silvertown just fell outside the boundary of the 1843 Metropolitan Building Act, many factories were built there that dealt with products that were unpleasant, noxious or even downright dangerous. Chemical factories abounded and manufactured or processed petroleum, caustic soda, creosote and even sulphuric acid. All this on the outskirts of the busiest metropolis on earth. Small terraced properties filled the gaps between the docks and these housed the factory workers.

As the First World War progressed, a caustic soda factory owned by Brunner, Mond and Co was ordered by the government to begin the manufacture of trinitrotoluene, commonly known as TNT, used in a wide range of munitions for the British troops fighting in the trenches. The company protested at the time, as the effects of handling TNT were well known. A large number of workers found that their skin would begin to turn yellow and they began to suffer from chest pains and nausea. However in September 1915 the company surrendered to growing government pressure and their factory began turning out TNT at the rate of nine tons a day…

A house wrecked in the Silvertown Explosion

On the evening of the 19 January, it seems that a fire broke out in the melt-pot room. Despite frantic efforts to put it out, some 50 tons of TNT ignited – with devastating consequences. The resultant explosion completely destroyed a large part of the factory and the properties in the surrounding streets, sending up a massive fireball and starting fires in the capital that could be seen as far away as Kent and Surrey. The sound of the blast was reportedly heard as far away as Norfolk. Flour mills on the southern side of the Royal Victoria Docks were flattened and other parts of the dock and warehouses were torn apart.

Those people who could, responded rapidly, but the unusual geography of this part of East London hampered rescue attempts. Seventy three people lost their lives and close to four hundred were injured, many seriously. Around seventy thousand buildings were damaged and the financial cost was estimated at £250,000 (an enormous amount at the time). Ironically, the death toll could have been so much more, given the level of devastation. Because of the time of day, many workers had left the factory, but had not yet retired for the night. This action may have saved hundreds as it was the upper floors of the properties that bore the brunt of the damage. A number of firemen lost their lives as their station was one of the properties brought crashing to the ground by the explosion.

Silvertown Fire Station after the explosion

The day following the explosion, the local authority took steps to oversee the rescue work and begin rebuilding their shattered community. Within two weeks, over 1700 men in the area were employed in repairing housing and as a result, by August of 1917, much of their work was complete.

An enquiry into the incident was set up and reached the conclusion that Silvertown was a totally unsuitable place to build a TNT manufacturing plant, and went on to criticise Brunner, Mond & Co for negligence in the running of the factory and for failure in looking after the welfare of their workers. The Government report remained secret until 1950…