When you approach Wapping Police Station from Wapping High Street, the modest building looks fairly innocuous. Almost dwarfed by the buildings of Aberdeen Wharf on the right and St John’s Wharf on the left, it is perhaps difficult to imagine that this is the birthplace of the oldest police force in the world.

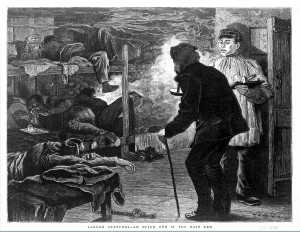

In the East End of eighteenth century London, importers were losing £500,000 of goods (that is a staggering £46 million at today’s rates) each year to theft. Estimates are not available for the theft of exports…

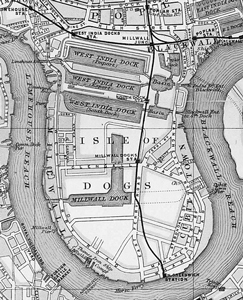

A way was sought to prevent or at the very least reduce the level of crime, and a proposal was put forward in 1797 to create a body of men who could patrol the Thames by John Harriot, an Essex Justice of the Peace. Following his plans being put before the West India Merchants and Planters Committees, funding was obtained and the creation of the Marine Police began on 2nd July 1798 in the building that still houses the Marine Support Unit of the Metropolitan Police.

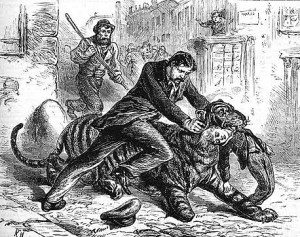

An initial force of around 50 river officers were trained and armed. They needed to be. It was estimated that almost 11,000 of the 33.000 people who worked the river trades were known criminals. The reaction to the new force was understandably hostile as the river thieves found that were losing an easy living.

Wapping Police Museum

A riot took place outside the station when around 2,000 men arrived with every intention of torching the place with the magistrates and some police officers inside. Whilst Harriot was able (and brave enough) to successfully disperse the riot, one of his officers, Gabriel Franks, was shot and died later in hospital. He became the first recorded police death.

The government became convinced of the benefits of the Marine Force (particularly after receiving letters confirming that the deterrent of a regular, patrolling force was working) and in July 1800 moved the force from private to public control. The force flourished, and became well established in the East End. In 1811, it was a Marine Police Force Officer who was first on the scene of the dreadful Ratcliffe Highway Murders. Eventually in 1839, the control of the Marine Force (together with other independent law enforcement groups like the Bow Street Runners) passed to the newly formed Metropolitan Police Force.

Nowadays, the station is home to the Marine Police Unit who continue to patrol the Thames – but the building also houses the wonderful Thames River Police Museum. This is to be found in what used to be the old carpenters workshop, and gives a fascinating glimpse into the origins of the world’s oldest police force.

Visits can be made to the Museum, on a strictly appointment only basis, and the request must be made in writing. Tours are run by two retired members of the River Police who guide you around the various exhibits, and upon entering the museum visitors are confronted with a wide range of historical artefacts. Many models exist of the type of vessels that they’ve used in the past, together with old nautical uniforms, weapons, trophies and such like.

One item that takes pride of place is the ensign of the ill-fated paddle steamer Princess Alice. This steamer, returning from an evening trip to Gravesend on 3rd September 1878 was struck by the coal carrier Bywell Castle and split in two. She sank within four minutes and over 650 people perished in the cold and polluted water of the Thames.

It was recommended at the enquiry into the Princess Alice disaster that the Thames Division should have steam launches to enable them to respond quicker to emergencies rather than the rowing boats that had been previously used…

Should you wish to visit the museum, please send your enquiries to:

Thames Police Museum

Wapping Police Station

Wapping High Street

Wapping, London, E1W 2NE

And enclose a stamped self-addressed envelope.