The young German sat in the communication hut in Athens at the end of October 1941, and took out a complicated machine of wheels and cogs. Plugging in his coding machine, he began to transmit a message of around 4000 characters to a secret Army location in Vienna. Annoyingly, after a few minutes, he received an uncoded message back from the recipient asking for retransmission as his message had not been received correctly. He shook his head in frustration and with a degree of irritation began to transmit the entire message again forgetting, in doing so, to alter the key settings for the machine. It was the break the staff at the code breaking HQ at Bletchley Park in the UK had been waiting for. The details that needed to be broken were fed into Colossus, the huge electronic computer, designed and built by Tommy Flowers – one of the East End’s – and the world’s unsung heroes.

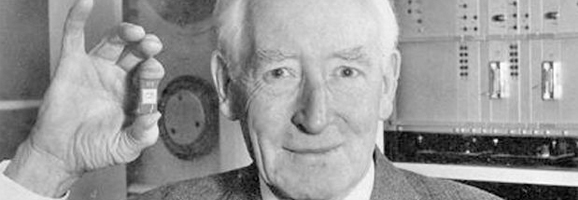

Tommy Flowers was born a few days before Christmas on 22nd December 1905 at 160, Abbott Road, Poplar. He was always a practical child – indeed, when told about the imminent arrival of a baby sister, he declared a preference for a box of Meccano!

Tommy Flowers

His father was a bricklayer by trade, but young Tommy decided to pursue a career in Mechanical Engineering. He began a four year apprenticeship at Woolwich Arsenal, and subsequently enrolled in evening classes at the University of London where he obtained a degree in Electrical Engineering.

In 1926, Tommy Flowers joined the telecommunication branch of the General Post Office – the GPO – and he took up a post at their Dollis Hill Research Station in 1930. He was still just 25 years old.

The outbreak of the Second World War shocked the nation and in February 1941, Flowers’ Director, W Gordon Radley approached the studious young engineer, explaining that he had been contacted by Alan Turing, from the Government’s code-breaking Station X at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire. He explained that he had received a request for Flowers to build a decoder for the Bombe Machines that Turing had developed to help break the German’s Enigma Codes.

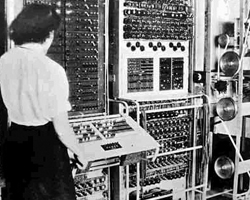

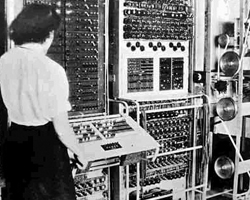

Looking at the problems Bletchley Park were having with their existing machine, Flowers proposed an electronic system – a massive machine using 1800 vacuum tubes (commonly referred to as valves) which took up a huge amount of space. Flowers christened his creation ‘Colossus’.

Previous versions had used only 150 valves, and some at Bletchley Park were sceptical about the use of valve technology at all. Famously, Flowers used much of his own funds to purchase his requirements for the new machine. It was reported that when he first told the military top brass it would take a year to build, they laughed at him and said ‘the war will be well and truly over by then – it’s not worth the effort’…

Alan-Turing

Colossus MK 1 proved that Flowers knew his craft. Whilst valves were prone to being notoriously temperamental and were constantly breaking down, Tommy Flowers recognised from his work as a GPO Engineer that things usually went wrong when machines were being continuously switched on and off. As a result, Colossus was left switched on in what Flowers described as a ‘stable environment’, and the problems that had plagued previous machines were averted.

By now, the Germans had begun to develop an updated and even more difficult coding machine, Lorenz, which pushed Colossus to its limits.

Undaunted, Flowers began work on a Mark 2 Colossus which came into service on 1st June 1944 and immediately provided vital information of Hitler’s thoughts prior to the D-Day landings that were planned for a few days later.

Tommy Flowers contribution to shortening WWII cannot be overstated. After the war, the government granted him £1000 (the payment of which did not even cover Flowers’ personal investment in purchasing the equipment he needed to build Colossus.) It is a testament to the character of the man that he shared the amount with his co-workers, keeping just £350 for himself – a decent sum for 1945 but a tiny amount for the man credited with building the first modern computer.

Perhaps ironically, Tommy Flowers applied for a bank loan to build another machine just like his prototypes, but was turned down as the bank refused to believe such a machine could be constructed. Adherence to the Official Secrets Act meant he could not tell the bank that he had already built several…

The Colossus Computer

After years of being unable to discuss his work with the world, restrictions were finally lifted in the 1970’s and his story was able to be told. He was awarded an MBE and a Doctorate from Newcastle University. Many still consider this ‘too little, too late’.

Tommy Flowers eventually died of heart failure on 28th October 1998, leaving a wife, Eileen and two sons.