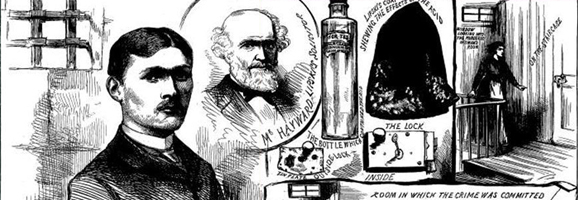

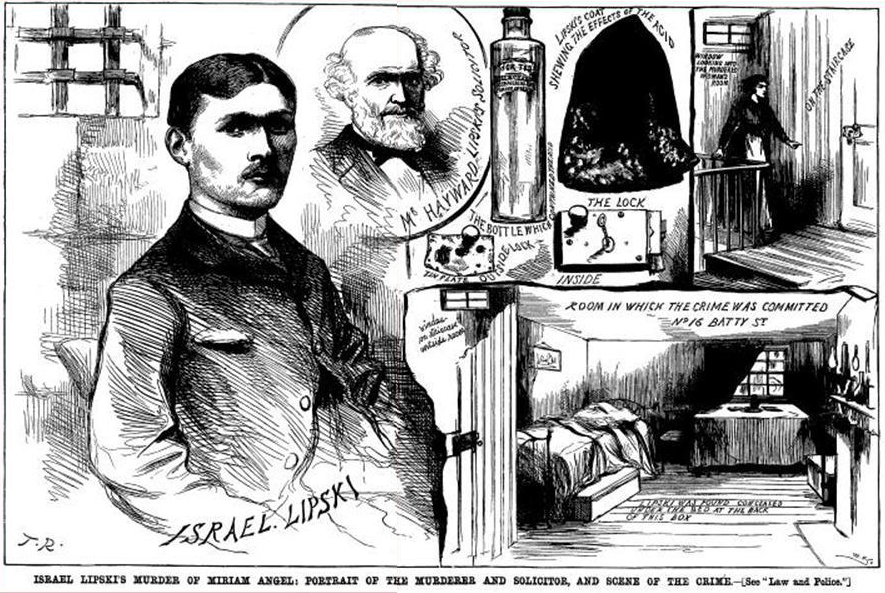

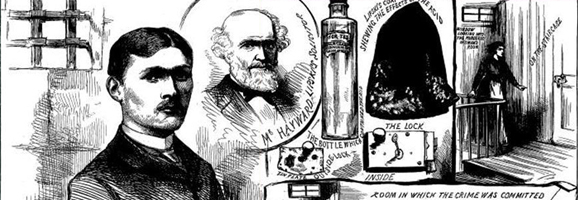

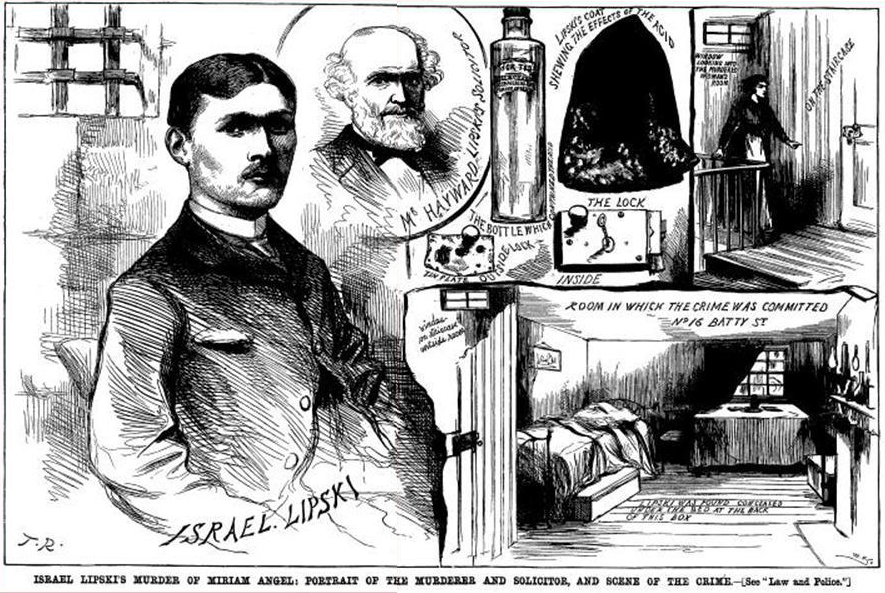

Shortly before lunch on Tuesday 28th June, 1887, the Whitechapel Police burst through the door of 16 Batty Street, having been alerted by other tenants that the occupier, a young woman called Miriam Angel had not been seen that morning. Upon entering the room, the police found the woman lying naked, dead on her bed with evidence of Nitric Acid burns around her mouth, and over her hands and breasts. She was found to be six months pregnant at the time.

Lying partly hidden under her bed was the unconscious body of Israel Lipski, a Polish Jew who lived in the same house. Given a sharp slap to the face, he awoke, and was duly arrested by the Police for the murder of the victim.

Israel Lipski (1865 – August 21, 1887) was born Israel Lobulsk, and had lived in the East End of London for some time. Described as a mild-looking, open-faced young fellow of just 22, Lipski worked as an umbrella stick salesman who employed two other Jews, Harry Schmuss and Henry Rosenbloom. After being dragged from beneath the bed, it was discovered that Lipski too, had some acid burns inside his own mouth, and Lipski protested his innocence claiming the crime had been committed by Schmuss and Rosenbloom. Nevertheless, the Police placed him under arrest while he lay in the London Hospital, Whitechapel Road.

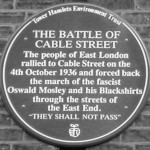

Lipski was tried and sentenced to death, but the trial was dogged with controversy, with claims of anti-Semitism levelled at the Judge and Jury. The then Home Secretary, Henry Matthews, showed apathy towards Lipski’s plight and he was duly hanged at Newgate Prison Yard on the morning of August 21st 1887.

So, was Lipski innocent? Reproduced below is an account of the trial taken from the Southland Times in October 1887 and the reader can decide for themselves.

“The prisoner and his victim (a young married woman named Miriam Angel) lived in the same house in Batty Street, Whitechapel, Lipski occupying a top back room, where he carried on the trade of a manufacturer of walking sticks, having a man and a boy as his assistants. On the morning of the 28th of June the husband of Miriam Angel rose at six, and went to work, leaving his wife in bed. At seven o’clock Lipski let into the house the boy who worked for him, and then went out himself to make some purchases. Among these was an ounce of nitric acid or aqua Fortis, which he procured from an oilman in Backchurch Lane. About nine o’clock Lipski asked his landlady to fetch him some coffee, it was duly brought but Lipski was not in his room, and on the landlady calling upstairs to him the boy replied that his master was not there. The theory of the prosecution was that just about this time Lipski had entered the room where Miriam Angel was in bed.

About eleven in the forenoon the people of the house began to be uneasy about Mrs Angel, who usually came down between eight and nine. Soon afterwards the handle of the door was tried, and it was found to be locked on the inside. The door was burst open, and the woman was found lying dead on the bed. A medical man, who was at once sent for, deposed that when he was called Miriam Angel had been dead about three hours. There was no rigor mortis. She was without clothes, and her hair was dishevelled; there were stains of nitric acid on her mouth, her face, her breasts, and her hands, which were covered by the burning fluid. The right eye was discoloured, and over the right temple was a patch of extravasated blood, where the muscle had been reduced to a pulp by the infliction of (the doctor held) at fewest four violent blows. Stepping over the corpse and looking down between the bed and the wall, in search of the bottle of poison which he naturally thought must be somewhere about, the medical man espied Israel Lipski lying in his shirt sleeves on his back, partially under the bed. He was unconscious, but on the doctor hitting him a smart slap on the face he opened his eyes wide. The police took him towards a window, and it was then seen that his lips were stained with nitric acid. He was asked in English and German what he had taken, but he made no reply. He was removed to the hospital, but, as from the first he had been the object of suspicion, the police never left him until he was formally charged with the murder, and a constable in plain clothes sat by his bedside day and night until he was convalescent.

Meanwhile a post-mortem examination of the remains of Miriam Angel had been made. It was found that the back of the throat was charred, and that a considerable quantity of nitric acid had gone down through the larynx and the trachea into the stomach, indicating that it had been poured down the throat while the victim was in a state of insensibility. But how, it may be asked, did she become insensible? The doctor was of opinion that the four blows on the temple had been fully sufficient to stun the deceased young woman, and that it was not until she was stunned that the poison had been administered to her. It was estimated that half an ounce of aqua Fortis had been given to her and that the immediate cause of death was suffocation by the acid going down the windpipe and closing the air passage. As regard Lipski, the medical evidence was to the effect that he had taken scarcely enough aqua Fortis to produce unconsciousness, but that the state of syncope was the result of mental perturbation.

In fine, the hypothesis of the prosecution amounted to this: that there was a small window commanding a view of Mrs Angel’s room; that the murderer, whoever he was, had seen Mrs Angel in bed from that window; that he came downstairs and entered her room for an immoral purpose; that, foiled in his design, he dealt his victim the blows which had produced insensibility, and that he then poisoned her, and ultimately, frenzied by horror, remorse and shame, endeavoured to commit suicide himself. The bottle which had contained the nitric acid was found; but it is not known whether the key was in the door, which was found to be locked inside. If the key was there, there can be no possible doubt as to Israel Lipski having been the murderer of Miriam Angel. The assistant to the oilman in Backchurch Lane swore that, to the best of his belief, the man who on the morning of the 28th June purchased from him a pennyworth of aqua Fortis was Israel Lipski, who explained that he wanted the stuff for the purpose of staining canes, and that the oilman’s assistant warned him that the acid was poisonous.

This explanation was as feasible as it would have been had Lipski said at the oil shop that he was a copperplate engraver, and that he required the aqua Fortis to bite in a plate withal. But what did he want in Miriam Angel’s bedroom in his shirt sleeves and with a bottle of aqua Fortis upon him; and, if the key were in the lock of the door which was found to be fastened on the inside, who on earth except Israel Lipski could possibly have committed the murder? Stains of nitric acid were found on his coat, and, singularly enough, there were acid marks on the clothes of Miriam Angel’s husband; but these marks, it was suggested, might have been caused by their having come in contact with the coat referred to. How did they come in contact? One of the most damaging features of the evidence against Lipski is the falsehood he told about having had a sovereign in his pocket on the morning of the murder, when it was conclusively proved that when arrested he only had a few shillings from his landlady. Next in importance in the array of facts marshalled against Lipski, was his own extravagant and incredible version of the affair. It was Inspector Final, of the Metropolitan Police, who was on duty at the Leman Street Station when Lipski was brought in on the morning of the murder partially insensible, and it was this official who found in his pocket only three shillings in silver and a pawn-ticket. The Inspector visited Lipski at the hospital, where the prisoner made, through an interpreter, the statement that at seven in the morning of the 20th a man who had worked for him came to him and asked for employment, and that he told this person to wait until he had bought a vice for use at his labour. He added that the tool-shop where he meant to buy the vice was still closed; that as he was going along he met another German workman, whom he knew, at the corner of Backchurch Lane; he then returned to the tool shop, which by this time was open, but he could not agree with the shopkeeper as to the price of the vice, and came away without it.

On his way home he again met the man whom he had seen at the top of Backchurch Lane, and who also asked him for work. Lipski told this man that he was going to have his breakfast, but bade him come along a little later on to the workshop, when he promised to engage him. He returned to Batty Street and asked the landlady to make him some coffee, and while it was being made he despatched the first man who had called on him at seven for some brandy.

Down to this point Lipski’s statement is plain sailing enough, but now comes the extraordinary and incredible portion of the narrative. He stated that, coming upstairs to the first floor, the man who had been sent for the brandy, and the man from Backchurch Lane, were opening a box in Mrs Angel’s bedroom; that they seized him by the neck, threw him to the ground, forced open his mouth, poured poison down his throat, saying mockingly “There is your brandy.” Then they asked him whether he had any money, and he replied that he had nothing but the sovereign which he had given the first man to buy brandy with. “Where,” they proceeded to ask him, “was his gold watch?” He replied that it was in pawn, and indeed a pawn ticket for a watch was found in his coat pocket. They threatened him that if he did not give them the watch he would soon be as dead as the woman on the bed, meaning Miriam Angel, and according to his showing they crammed a piece of wood between his teeth to serve as a gag, knelt on his chest, and at last threw him under the bed, where he lay unconscious. It is but fair to the wretched man now in the condemned cell at Newgate to mention that Mr Calvert, the honorary physician at the London Hospital, found on examining Lipski that there was an abrasion in the inside of his mouth, indicating that some foreign substance had been thrust in; but Dr Redmayne, who had used the stomach pump on Lipski, said that the abrasion might have been caused by the instrument in question. Did he struggle while the stomach pump was being used? All that the defence could urge was that, although Miriam Angel had undeniably been killed by nitric acid, there was not sufficient evidence to show that Lipski was the man who bought the pennyworth of corrosive fluid on the morning of the murder, and there was an entire absence of motive so far as Lipski was concerned for the commission of so horrible a crime.

The jury, however, took the view shadowed forth in his summing up by Mr Justice Stephen; that the murderer of Miriam Angel entered her room under the influence of unlawful passion; that, baulked in his design, his passion turned to homicidal fury; and that in a reaction of shame and terror he had taken a dose of the same poison that he had given to his victim. If this theory was probable, continued the learned judge, the murder was much more likely to have been the work of one man than of two. So the jury thought; and they found that the one man was Israel Lipski, and that he was guilty of the cruel murder of Miriam Angel.”

Strange to say Lipski’s counsel was convinced that the condemned man was innocent and exerted himself to obtain evidence to prove him so. So urgent was he that the Home Secretary respited Lipski for a week in order to give his solicitor time to bring proof. Lipski, however, confessed that he did the deed before the week was out and was therefore executed. It was supposed that he must have surprised his victim asleep as she was a young woman of robust physique and more than a match for the puny wretch in a fair struggle.