If you had asked anyone in the East End where Brady Street Jewish Cemetery was in the late 1800s, they would have stared at you blankly. Unsurprising really, as the thoroughfare now known as Brady Street was then known as North Street, and some years before that, Ducking Pond Lane.

A short stroll away from bustling Whitechapel Tube Station, Brady Street is a nondescript aside off the Whitechapel Road, but behind a high brick wall on the western side of the road hides a quiet and calm cemetery – part of the strong Jewish influence that had come to dominate Spitalfields and the surrounding areas.

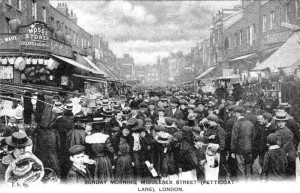

Yiddish signs were already an everyday sight in the Victorian East End – theatre posters and newspapers of the time carried the language and Jewish culture began to permeate the already ancient buildings. By the turn of the century, for example, there were 15 kosher butchers in Wentworth Street alone.

A number of smaller synagogues called ‘chevras’ had been built in the area and these provided welfare to the Jewish community as well as being a place of worship. It became obvious therefore, that the Jewish people in the area needed somewhere to bury their dead.

Map showing the ‘Jews Burial Ground’ in North Street

Brady Street Jewish Cemetery (It was marked as the much brasher ‘Jews Burial Ground’ in maps of the day) was originally leased by the New Synagogue at the end of May 1761 – The freehold transferring to them when they bought it in 1795.

When the cemetery became full in the 1790s, the decision was made to place a four foot layer of fresh earth over the central part of the site, creating a flat topped mound, called the ‘Strangers Ground’ which was used for subsequent burials. Because of the additional layer, the headstones are placed back to back to identify the ‘occupants’ of the graves.

Eventually, the site was given notice that burials should discontinue from the beginning of February 1856. The closure date was extended a number of times, but the cemetery eventually closed on 31st May 1858.

However, in 1980, the local council began proceeding to apply for a compulsory purchase order so the site could be redeveloped. As the law stands, any cemetery that has had no internments for 100 years can have its occupants removed and the land reclaimed for commercial use.

Victor Rothschild’s Tomb

In order to protect the cemetery from this fate, a one off internment took place in 1990; that of the third Baron, Nathaniel Mayer Victor Rothschild, who was buried by his ancestor Nathan Mayer Rothschild – founder of the British branch of the Rothschild banking dynasty. As a result of this action, the site cannot be developed until at least 2090.

Access to the cemetery is limited, but you can still see into one corner by peering through the ivy covered wrought iron gateway near its entrance.