The men and women of the East End were well used to bad smells. The noisome vapours of the tanneries (who frequently used dog turds in their preparation of the tanned hides) hung around Spitalfields like an invisible fog, but as summer turned into the autumn of 1875, people passing Henry Wainwright’s warehouse and packing depot at 215 Whitechapel Road wrinkled their noses at the appalling stench that emanated from his premises. What was that god-awful smell? Appalled Londoners were soon to find out…

37 year old Henry Wainwright appeared to be a highly respectable, hard-working businessman who had inherited his family’s brush-making business at 84 Whitechapel Road, in the East End of London.

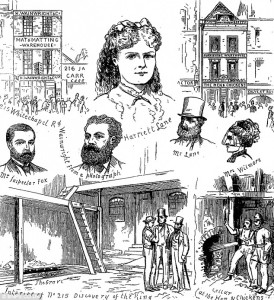

Henry Wainwright

As well as being a successful manufacturer and warehouse owner, Henry was a temperance lecturer, living with his wife and four children in a comfortable house in Tredegar Square. But Henry Wainwright was not all he appeared to be on the surface. Despite his apparent comfortable home life, Henry had a more complicated side.

Henry Wainwright had met a young, attractive 20-year-old milliner’s apprentice called Harriet Lane in 1871. Totally infatuated, he set up a home for her as his mistress in a property at 70 St Peter Street, Mile End, where Harriet took to calling herself ‘Mrs Percy King’. Over the course of the next two years, the love-struck pair had a couple of children. However, the financial cost of trying to run the two homes was playing havoc with Henry’s financial situation.

He tried moving Harriet and the two children to cheaper accommodation in Sidney Square, but this did little to alleviate the problem, and Henry Wainwright found himself moving ever closer to bankruptcy. By 1874 his business was starting to founder, and his debts were mounting.

To compound the problem, Harriet liked to drink, becoming loud and demanding when she had had a few too many. She was continually demanding additional money from Henry to help support his two illegitimate children, and eventually she began to threaten to expose their affair to his wife if he did not increase payments.

Harriet Lane

In desperation, Henry began to hatch a plan and turned to his brother, Thomas, for assistance. Without divulging his eventual intentions he asked Thomas to pretend to woo Harriet through a series of written letters, which Thomas duly did, using the pseudonym Edward Frieake.

At 4pm on Friday 11th September 1874, an excited Harriet arranged for a couple of friends to look after her children and she left the property in Sidney Square. Wearing a grey dress (with new shiny black buttons she had sewn on that morning), a black bonnet, and a black cape trimmed with lace and velvet, she carried a new umbrella and had her night clothes wrapped in a neat parcel. From then on, all communication with her friends ceased, and she appeared to vanish into thin air.

Later that day, a small group of men working outside Henry Wainwright’s warehouse at 215 Whitechapel Road heard what they thought to be three gunshots. A cursory examination of the immediate area failed to discover the cause, and they continued with their work…

When the friends expressed concern over Harriet’s disappearance, Henry Wainwright stated that he had given Harriet 15 Shillings and informed them that to the best of his knowledge, she had travelled to Brighton. Shortly afterwards, the friends received a letter from ‘Edward Frieake’ explaining that he had asked the young Harriet to marry him and they were going to Paris to live together…

Twelve months passed, but despite Harriet’s disappearance, Henry Wainwright’s financial situation continued to cause him problems. Finally, he made the fateful decision to sell the warehouse at 215 Whitechapel Road, where passers-by had started to notice the obnoxious odours.

On September 11th 1875, Wainwright went to the warehouse and used a spade to loosen the earth on a shallow grave that had been dug just below the floorboards. He had used lime chloride in an attempt to cover the foul stench of the rotting human remains he had buried there almost exactly one year ago. Using a small hatchet, he proceeded to dismember the decomposing body and wrapped the pieces into two heavy parcels, covered in black American cloth and tied with rope.

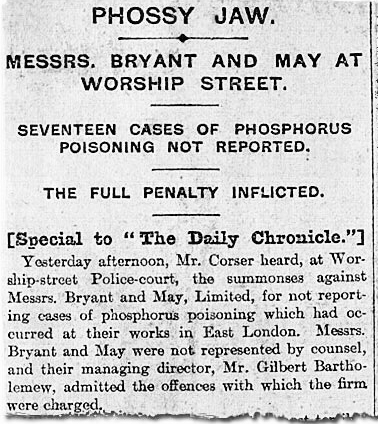

A Newspaper Clipping detailing the Henry Wainwright Murder

Wainwright then enlisted the help of an unsuspecting employee, Alfred Stokes, who he asked to help him move the two parcels. Stokes agreed, but was unable to contain his disgust at the two heavy, foul smelling packages Wainwright produced. Stokes was told to wait with the parcels while Wainwright went for a cab. While he was away Stokes stole a peek inside the largest parcel. As he opened it, the first thing he saw was a human head, and then a hand which had been cut off at the wrist. Appalled, he quickly repacked the parcel and waited until Wainwright returned.

Wainwright put the two parcels into the cab, instructed Stokes that he would see him later that evening, and departed. Stokes pursued the cab on foot until he saw two police constables by Leadenhall Street—He drew their attention to the cab, begging them to stop it, but they laughed at him and said, “Man, you must be mad”.

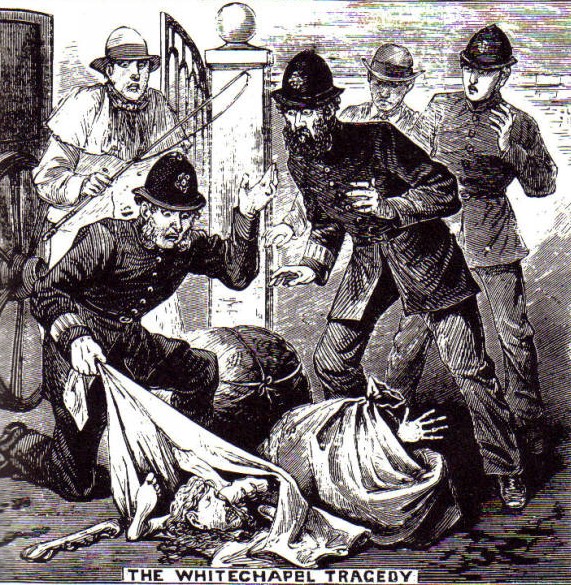

Stokes continued to run after the cab as it turned over London Bridge, eventually stopping outside the Hen & Chickens. He alerted two other police constables; PCs Turner and Cox, No. 48 and No. 290 and said “For God’s sake run after the man with the high hat with the parcels in his hand, there is something wrong.” This time, the two constables took Stokes’ protestations at face value, and as he left the cab, they accosted Wainwright.

As PC Turner reached for one of the packages Henry Wainwright said “Don’t open it, policeman, pray don’t look at it, whatever you do don’t touch it”. The policeman pulled the cloth package open and discovered that it contained part of the remains of a human body. As Cox went to get the cab, Wainwright attempted to bribe the police constable saying, “I will give you 100 shillings, I will give you 200 shillings and produce the money in twenty minutes if you will let me go“.

Henry Wainwright was subsequently charged with murder, and the police also tracked down and arrested his brother, Thomas. A search of the warehouse at 214 Whitechapel Road revealed the site of the shallow grave and patches of what appeared to be old blood.

In his testimony to the police, Alfred Stokes suggested that the body in the parcels was that of the missing Harriet Lane. Harriet’s family identified the body, although the features were largely unrecognizable. Shiny black buttons on the clothing matched those sewn on by Harriet the day she had left Sidney Square and some jewellery found in the warehouse grave was thought to have belonged to her. The victim had been shot in the head with a small calibre pistol, and the throat cut afterwards. Henry Wainwright was known to possess a gun of a type consistent with the murder weapon.

At his trial at the Old Bailey in November 1875, Henry Wainwright claimed that he had no idea what the parcels contained. His flimsy defence was that he had been asked by a mystery man to take the parcels from the warehouse for a sum of money. The jury deliberated, found Wainwright guilty and he was duly hanged on 21st December, 1875, at Newgate Gaol. His brother, Thomas Wainwright, was sentenced to seven years penal servitude as an accessory after the fact.

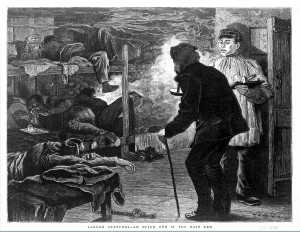

The discovery of Harriet Lane’s dismembered Body