Social deprivation was nothing new in the East End of London in the mid 1800’s, but it would be hard to imagine nowadays the plight of the Match Girls at Bryant and May’s factory in Worship Street, Bow.

William Bryant and Francis May (who were both Quakers) had originally imported red-phosphorus based safety matches from John Edvard Lundström, in Sweden, in 1850. However, as demand increased Bryant and May bought Lundström’s UK patent, building their new safety match factory in Bow.

They continued to use red phosphorus throughout 1855, but the product was much more expensive than the alternative – white phosphorus-based matches. Bryant and May found a ready solution in the East End – and began the use of child labour. At its height, the factory was to employ around 3000 East End children, predominantly girls.

The match girls, some as young as 13, worked from 6.30am until 7pm, with just two breaks, standing all the time, often eating any lunch at their workbenches, breathing fumes as they dined. In the factory, those girls known as “mixers,” “dippers,” and “boxers” were most exposed to the heated fumes containing this compound.

Phosphorus Necrosis or ‘Phossy Jaw’

However, the long hours were often just the start of the match girls’ misery. Many were struck down with a terrible disease – phosphorus necrosis – known by the colloquial term of ‘Phossy Jaw’. Those girls who suffered with phossy jaw would begin experiencing agonising toothaches and a swelling of the gums. Over a period of time, the jaw bone would begin to abscess.

The bones of the jaw would start to glow a greenish-white colour in the dark, and the decaying bone tissue would eventually rot away. The accompanying open wounds would run, giving off a foul-smelling discharge. Finally, in its advanced stages, the disease would lead to serious brain damage and death.

The exploitation of the girls came to the attention of a journalist and social activist called Annie Besant, together with her friend Herbert Burrows, who, following the disclosure that Bryant and May’s shareholders were receiving dividends of 20%, whist the girls were paid around 4 – 8 shillings a week (20 – 40p), published an article in her weekly paper ‘The Link’ on 23rd June 1888.

Annie Besant

After questioning several of the young girls at the factory, her shocking article likened the Bow factory to a “prison-house” and described the match girls as “white wage slaves” – “undersized”, “helpless” and “oppressed”.

She wrote – “Do you know that girls are used to carrying boxes on their heads until the hair is rubbed off and the young heads are bald at fifteen years of age? Country clergymen with shares in Bryant and May’s, draw down on your knee your fifteen year old daughter; pass your hand tenderly over the silky beauty of the black, shining tresses”.

Bryant and May reacted angrily to the accusations and tried to insist that each member of their workforce sign a prepared declaration contradicting the article. The girls refused and as a result, one of their number was dismissed on what was seen to be a spurious and made up charge.

By the end of that day – around half of the workforce, some 1500 women and girls – refused to work. Whilst the management attempted to backpedal and reinstate the sacked worker, the girls demanded other changes to their working conditions, particularly in relation to the unfair fines which were deducted from their wages.

By the 6th July 1888, the entire factory stopped work and a group of around 200 girls descended on the Fleet Street offices of Annie Besant and her newspaper. Annie Besant’s initial reaction was one of shock and dismay that so many of the women and girls were now effectively out of work with little or no means of support.

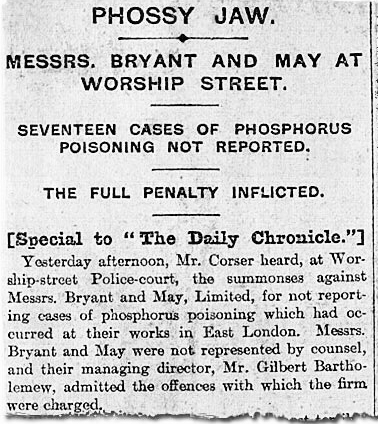

A newspaper cutting highlighting the issues

She helped the girls to coordinate a strike fund, and a number of other newspapers collected donations from readers. Prominent members of the Fabian Society including George Bernard Shaw, Sidney Webb and Graham Wallas became involved in the distribution of the cash collected.

The Member of Parliament, Charles Bradlaugh, spoke in the house on behalf of the girls’ plight, and a number of the match-girls travelled to the House of Commons to meet a group of MPs and increase the publicity and pressure on Bryant and May.

Finally, the factory owner William Bryant, concerned about the poor publicity, formulated a meeting on the 16th July 1888 where it was agreed that a number of the girls’ grievances, such as fines, unfair deductions and penalties and the creation of a separate dining area where meals could be taken without the danger of contamination from the phosphorus, would be met.

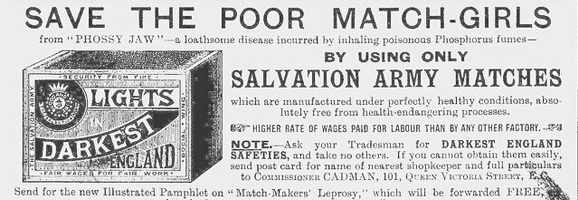

Besant and others continued to campaign against the use of white phosphorus in matches, and in an effort to try and combat the situation, the Salvation Army opened up its own match factory in the Bow district, using less toxic red phosphorus and paying better wages. However, the continued high cost of red phosphorus compared to white phosphorus caused its downfall and The Salvation Army match factory finally closed, ironically being taken over by Bryant and May, on 26 November 1901.

The Bryant and May factory in Bow