Ratcliffe Highway no longer exists as it did in the early part of the 19th Century East End. It derived its name from the red sandstone cliffs which descended from the high ground, where the road was situated, down to the marshes at Wapping in the south. Nowadays it is simply called ‘The Highway’ but then it was one of the main routes leaving London and was the site of two horrendous murder scenes that claimed a total of seven victims.

A little before midnight on the 7 December 1811, Timothy Marr, a Drapers shop owner, sent his maid Margaret Jewell out for some oysters (regarded as a much more modest meal than by today’s standards) and to run a small errand to pay a bakers bill.

He remained in the shop with his wife Celia, their 3 month old son and his young apprentice called James Gowan.

Margaret returned empty handed having failed in both her errands and found the front door locked and the house in semi-darkness. Hearing footsteps on the pavement behind her, she hammered the door knocker violently and in doing so, gained the attention of a George Olney, a local night watchman, who came out to find the source of the commotion.

Olney too, tried the door, but to no avail. His knocking roused the neighbour, a Pawnbroker called John Murray, who climbed over the adjoining wall at the rear of the building. The back door lay ajar and a weak light shone from inside the premises. Murray tentatively let himself in and entered the shop. The sight that met his eyes would stay with him forever…

He later recounted that “the carnage of the night was stretched out on the floor and the narrow premises so floated with gore that it was hardly possible to escape the pollution of blood in picking out a path to the front door”.

The Ratcliffe Highway Murder Location

He first discovered James Gowan, the young apprentice, who was lying on the floor about five or six feet from the stairs, just inside the shop door. The young boy’s skull was completely smashed, his blood was dripping through the floorboards, and his brains had appeared to have been pulverised and thrown about the walls and across the counters of the shop.

Appalled, Murray rushed to the front door to let the night watchman in, but in doing so he came across another dead body, that of Celia Marr. She was lying face down on the floor, and she too, had suffered massive head trauma, and was still bleeding profusely. Murray quickly let in Olney and the pair began searching for Marr. They found the shop owner behind the counter, battered to death. Murray and Olney then rushed to the bedroom of the infant Timothy. Both men recoiled in horror as they found the baby dead in his cot. The entire side of his face had been crushed and his throat had been slit so severely that his head was nearly severed from his body.

The first Police Officer on the scene was from the Marine Police Force (the Metropolitan Police had yet to be created) and he was baffled by what he saw as a lack of motive. Nothing in the shop appeared to have been stolen, there was still a quantity of money in the till and a large amount of cash stored in a bedroom chest of drawers was untouched.

Looking for a murder weapon, Horton found a chisel and a long handled shipwright’s hammer, commonly called a maul, covered in blood, and with human hair sticking to it…

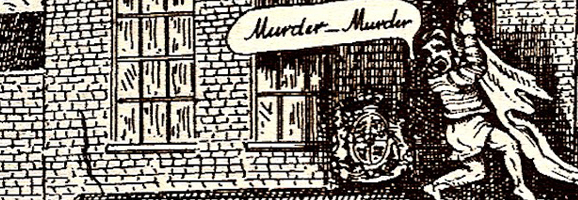

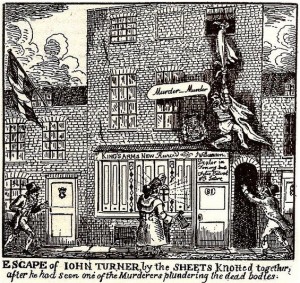

Twelve days later on the 19th December at a Tavern called the King’s Arms in New Gravel Lane, a short distance from the original murder site, a crowd of people were startled by the cries of ‘Murder – they are murdering the people in the house’ and the sight of a near naked man climbing down from the first floor windows using knotted bedsheets. The man, John Turner, was a lodger and as he reached the ground he was shaking and crying uncontrollably.

The crowd soon forced open the doors to the tavern to find the owner and publican, John Williamson, his wife Elizabeth and their maid Bridget Harrington. All three had been murdered violently. As before all showed evidence of massive blows to the head, fracturing their skulls and once again all three had had their throats cut, with Elizabeth Williamson’s neck being severed down to the bone.

A ramshackle force of constables from various parishes and a group of Bow Street Runners was quickly convened, and it soon began a series of arrests. In fact, following rewards being offered both by government and various public bodies, over 40 false arrests were made before a leading suspect came to the attention of the officials. A seaman called John Williams who had lodged at a public house called the Pear Tree, just off The Highway in Wapping, was noted by his roommate to have returned after midnight on the nights of both sets of murders. The roommate claimed Williams had a long standing grievance against the first victim Mr Marr from when they were both shipmates.

Post Mortem sketch of John Williams

Despite the scarcity of anything but purely circumstantial evidence against Williams, he was duly arrested and held to appear in front of Shadwell Magistrates. He never came to trial. On the 28th December, John Williams used his own scarf to hang himself from a bar in his cell. However, this was not about to stop the judicial process in its tracks, and the hearing continued, with the court finally deciding that Williams had indeed been guilty of the horrendous crimes. His suicide merely served to convince the court of his guilt, and he was duly convicted as the sole perpetrator of the murder of the seven victims.

However, the case has a more unusual footnote. Although Williams was now dead a group of citizens took the law into their own hands ‘to ensure that his corpse could not rise to repeat his crimes’. As a result, Williams’ body was taken by open cart and paraded past the scenes of the crimes. The group finally halted at the crossroads formed between Cannon Street and St Georges Turnpike, where a small grave had been dug. The body was then bundled into the open grave – and a stake driven through John Williams’ heart. Quicklime was added, the pit was then covered over, and the burial concluded.

NB – The eagle eyed amongst you may recognise this murder as forming the basis of a story in the TV Series – Whitechapel…