The young blonde actress looked about her bemusedly. The cold damp field didn’t look very Hollywood to her – even the mud had been painted green to look like grass and she was starting to sink slowly into it.

Although it was a bitterly cold February morning, all her co-actors were wearing nothing but bikinis and swimsuits and were being addressed by the director, Gerald Thomas, on the set of ‘Carry on Camping’.

Barbara Windsor in Carry on Camping

‘Right love, we’ll attach some fishing line and a hook to your bra, and Bert, the props man will pull it off’

So with only Kenneth Williams and Hattie Jacques (and essential film crew) in front of her, a 32 year old Barbara Windsor created one of the most memorable comedy vignettes to have appeared in British film history.

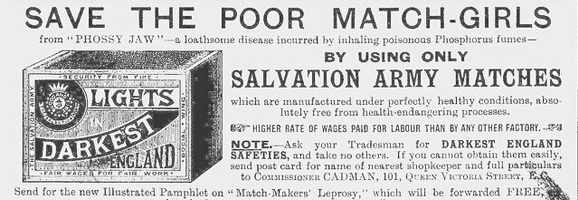

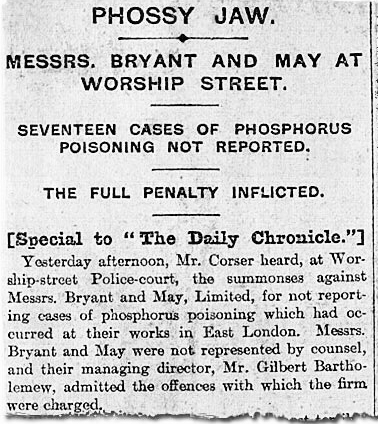

Born Barbara Ann Deeks in August 1937 – in the London Hospital, in Whitechapel Road to parents John and Rose Deeks, Barbara’s family had both East End and Irish connections. Barbara’s paternal great-grandmother had fled from the terrible Irish potato famine and had settled in the East End, eventually finding employment as one of the infamous match girls.

Barbara Windsor was an only child, and her mother made no bones of the fact that she had been hoping for a boy. When John Deeks left to fight in the war, Barbara was evacuated to Blackpool.

Barbara was taken in by Florence and Ernest North, and Florence soon spotted some potential in young Barbara, writing a letter to Rose Deeks asking to be allowed to send her to Norbreck Dancing School with her own daughter Mary.

Once there, Barbara took to singing and dancing like a duck to water, and upon returning to London, her mother paid for elocution lessons and enrolled her in the Aida Foster Acting School in Golders Green. She made her stage debut at 13 and aged just 15 made her West End debut in the chorus of the musical ‘Love from Judy’, a role she continued for two years.

In 1954, aged 17, Barbara Windsor made her film debut in ‘The Belles of St Trinians’, before continuing her stage career with Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop in Stratford East, performing in ‘Fings Ain’t Wot They Use To Be’ and Littlewood’s film, ‘Sparrers Can’t Sing’.

It is probably for her career in the immensely successful ‘Carry On’ series of films that Barbara Windsor became a star. She recalls in her autobiography ‘All of Me – My Extraordinary Life‘ that she had an argument with co-star Kenneth Williams in her first film, where he accused her of fluffing her lines. In a scene which required him to wear a beard, she drew herself to her full four feet ten and a half inches and shouted out “Don’t you yell at me with Fenella Fielding’s minge hair stuck round your chops, I won’t stand for it”.

Kenneth Williams was said to have clapped his hands together and grinned, saying ‘Haaaah – isn’t she wonderful?’ They became lifelong friends.

Barbara Windsor went on to make nine Carry On films, although she is so memorable many people think she actually appeared in a lot more.

Barbara Windsor with Ronnie Knight and Reggie Kray

Barbara’s off stage life was complicated as that on screen, with a string of affairs, a total of five abortions (three before she was 21) and three marriages. She lost her virginity at 18 to a ‘flash Arab’. Her affair with her Carry On co-star Sid James has been well documented and she was also romantically linked to Bee Gee Maurice Gibb.

Her first marriage was to small time crook Ronnie Knight, and through him, she became associated with the Krays, initially going out with the twins older brother Charlie (who she described as looking ‘a bit like Steve McQueen’), before sleeping with Reggie Kray. She later married Stephen Hollings, an actor, in 1986 before their divorce in 1995, and is now married to former actor Scott Mitchell.

Barbara Windsor cemented her East End credentials when in 1994, she appeared as Peggy Mitchell in the long running BBC soap opera ‘Eastenders’, admitting when she joined the soap that she had been a ‘scared little lady’.

Barbara Windsor as Peggy Mitchell

She continued to play a major part in the show, winning the British Soap Award for Best Actress honour in 1999 until a tearful farewell on the 10th September 2010 (although she did make a small comeback for one episode in 2013).

Her awards didn’t finish there however, as she was made an MBE in the 2000 New Years Honours List, and went on to become Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 2016 New Years Honours.

In 2012, Barbara Windsor became patron of the Amy Winehouse Foundation, and in 2014 was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of East London.

However, 2014 also found Barbara being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, but it was not until May 2018 that her husband, Scott Harvey Mitchell revealed her condition to the public for the first time.

On her 82nd birthday in 2019, she and her husband became ambassadors for the Alzheimer’s Society, but the clock was already ticking.

Sadly, this pocket powerhouse, who brought so much joy to millions passed away with the disease at 8.35pm on 10th December 2020.

RIP Dame Barbara Windsor.