People in the East End in 1857 were an impassive and stoical lot. The area along St George’s Street, formerly Ratcliffe Highway, was already infamous for the series of ghastly murders that had taken place there 45 years before (more here), but despite its notoriety, the two women peering at the jewellery in the pawnbrokers shop next door to Mr Charles Jamrach’s Menagerie had other things on their minds. Suddenly, one of the women noticed a strange reflection in the shop window, and turned. She stifled a scream and pulled her companion into the shop doorway, as a fully grown Bengal Tiger padded past them, carrying a small boy in its mouth…

Charles Jamrach was born in Hamburg, Germany in March 1815 where his father, Johann Gottlieb Jamrach, was chief of the Hamburg river police. As part of his job, Jamrach Senior would find himself having to board vessels on the busy waterway and he soon built up a reputation amongst the sailors for purchasing any exotic creatures they had brought back with them from their travels. He rapidly established himself as a dealer in birds and wild animals – and set up branches in the great ports of Antwerp and London.

Young Charles was fascinated by the myriad animals, birds and insects in his father’s shop and following his father’s death in 1840, Charles Jamrach moved to take over the London branch of the business, developing the existing premises into a bird shop and museum in St. George Street known as ‘Jamarch’s Animal Emporium’, a menagerie in Bett Street, and a warehouse in Old Gravel Lane, Southwark.

Jamrach’s Menagerie

The business thrived, partly due to Jamrach’s location, close to The London Docks and partly due to his ever expanding customer base – the London Zoological Gardens had been loaned an Elephant which he was confident they would buy, and following a devastating fire at P.T Barnum’s Circus in 1864, it was Jamrach’s Menagerie who was responsible in restocking it with animals.

A Mr John Edward Gray who was keeper of zoology at the British Museum also named a snail that had been forwarded to him by Charles Jamrach Amoria jamrachi in his honour.

A reporter visiting his premises wrote that “The museum includes tropical beetles glorious with shards of green and gold, and tropical butterflies like tropical blossoms, or costliest satin and velvet embroidered with creamy lace, and be-dropt with precious metals and precious stones”…

As one can imagine, Jamrach’s stock varied considerably, dependant as it was on the ships that were docking in London, but a contemporary article of the time shows the extent and prices of the animals on offer.

Zebras – £100 – £150 each

Camels – £20

Giraffes – £40

Ostriches – £80

Polar Bears – £25

Other Bears – £8 – £16

Leopards – £20

Lions – £100

Tigers – £300

On one fateful day in 1857, Charles Jamrach had just taken delivery of a large number of animals which had been brought in on ships arriving in London Docks from their voyage to the East Indies. The animals were taken to the Bett Street repository with Jamrach himself overseeing operations. To ensure that the fully grown Bengal tiger in one crate had no opportunity to maul his workmen, Jamrach instructed that the wooden crate containing the beast was placed with its barred opening facing the wall. However, the strength of the animal had been underestimated – and as another crate containing leopards was being unloaded, Jamrach and the workmen were horrified to hear a crash and to discover that the tiger had pushed out the back of the crate with its hind legs and was now prowling around the yard.

Jamrach and the Tiger

The tiger stalked its way into the street where a curious boy, around nine years of age, reached out to stroke the back of the strange creature that had appeared before him. In an instant, the tiger whirled and gripping the boy’s shoulder in his jaws, ran off down the street in the direction of the docks.

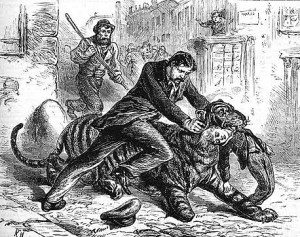

Jamrach dashed after the animal and upon catching up with it, grabbed the tiger by the loose skin of its neck and tried to wrestle it to the ground. He succeeded in tripping it by putting his own leg under the tiger’s hind quarters, but the animal would not relinquish its hold on the now terrified boy. It was not until his workmen arrived and dealt the animal several blows to the head, that the stunned animal finally let go of the child. Shaking itself free, the tiger then turned tail and headed back to the menagerie yard and the relative safety of an empty crate, where it was recaptured.

The event is commemorated by a statue that stands near the entrance to Tobacco Dock today.

The boy was taken to hospital but, astonishingly, found to be virtually unharmed save for a severe fright and a few scratches. Jamrach offered the boy’s father compensation of £50, but the father rejected the money and decided to bring a court action against him for damages.

At the trial the judge sympathised with Jamrach, saying that, instead of being made to pay, he ought to have been rewarded for saving the life of the boy, and perhaps that of a lot of other people.

The Boy and The Tiger Statue, Tobacco Dock

The judge, however, had to administer the law as he found it, and reminded Jamrach that he was responsible for any dangerous consequences brought about as a result of his business. He suggested, however, as there was not much hurt done to the boy, to put down the damages as low as possible. The court subsequently set a penalty of £300, of which £240 went to the lawyers as costs!

News of the tiger’s escape and notoriety soon got around, and within a few days of the end of the hearing, Jamrach was able to sell the animal to a Mr Edmonds, of Wombwell’s Menagerie for £300.

Charles Jamrach died in Bow on 6 September 1891, leaving two sons, Albert and William. The business continued for some time, but began running into difficulties during the First World War, and after his son Albert died in 1917, the firm finally closed its doors in 1919.

The final words are from an article written by a journalist in 1879 who had been invited to visit Jamrach’s Menagerie and who wrote “I have nothing further to state, except to assure my readers of naturalist tastes that, for whatever they want, from a hippopotamus to a humming-bird, Jamrach’s is the very place to go to”.