From Hell

There have been numerous films based, albeit loosely, on the ‘career’ of the East End’s most infamous son, Jack the Ripper. Given the scope for speculation, it is perhaps surprising that there have not been more – but, for dramatic effect, most are inaccurate in their historical portrayal of facts. There is of course nothing wrong with this, as long as the viewer remembers that they are merely dramatic pieces – it’s the difference between reading a novel or an encyclopaedia.

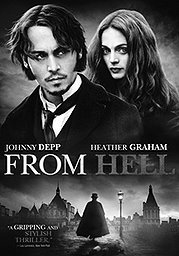

The 2002 film ‘From Hell’ is one such story. Starring Johnny Depp and Heather Graham, this film has a graphic novel feels to it – unsurprising as that is how the story started out. So firstly, why ‘From Hell’? In one of the letters written by the ‘real’ Jack the Ripper, this was the return address he used on the correspondence.

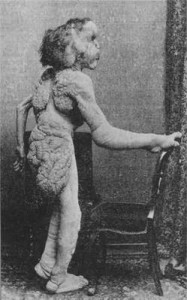

Set in 1888 in the East End of London, the film starts by highlighting the plight of the unfortunate poor who spend their appalling lives in the city’s deadliest slum, Whitechapel.

Street Gangs force prostitutes to walk the streets for a living, and Mary Kelly (Heather Graham) and her small clutch of companions lives their miserable existence, consoling themselves with the fact that things can’t get any worse. However, when their friend Annie is kidnapped the women are drawn into a conspiracy with connections far higher up the social ladder than any of them could possibly imagine.

Annie’s kidnapping is rapidly followed by the gruesome murder of another of their group, Polly, and it becomes apparent that the women are being hunted down, one at a time. Even by the standards in Whitechapel at the time, this murder attracts the attention of Inspector Fred Abberline (played by Johnny Depp with a half decent cockney accent), a talented yet troubled man whose police work is often aided by his ‘psychic’ abilities, an ability he attempts to enhance by frequent visit to the numerous Opium Dens prevalent in the area at the time. Abberline is portrayed as an opium addict and when “chasing the dragon” he is able to have visions of the future, a certain psychic ability that allows him to solve cases.

Being Hollywood, Abberline becomes deeply involved with the case, which becomes personal when he and the attractive Mary begin to fall in love. However, as Abberline gets closer to the truth, the Whitechapel area is becoming more and more dangerous for his love interest, Mary, and the other girls. Whichever individual is responsible for the gruesome acts of murder and evisceration is not going to give up his secret without a fight….

The film is entertaining enough, but sharped eyed members of the audience will spot a number of errors that seem to have been overlooked for ‘poetic license’ purposes.

We are shown a shot of the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel. However, it only gained its “Royal” status in 1990 – for the rest of its previous 250 years history, from when it was constructed on its present site in 1757, it was simply called ‘The London Hospital’.

A short while after the second murder, Inspector Abberline refers to “Jack the Ripper”. However, the murderer was not to become known by that name until the double event murder and receipt of the “Dear Boss” letter, which took place 4 weeks later.

Like most film and Television versions of the Ripper murders, From Hell shows the Ripper’s victims as being considerably younger and more attractive than in real life. Sadly, the vast majority of the prostitutes in the East End were gin soaked and riddled with disease, which quickly robbed them of their looks. Hollywood lets us down again….