The London Docks occupied a total area of about 30 acres (120,000 m²). They consisted of the Western and Eastern docks which were linked by the short Tobacco Dock. In turn, the Western Dock was linked to the River Thames by Hermitage Basin (in the south west) and by Wapping Basin (to the south).

The Eastern Dock joined the River Thames via the Shadwell Basin to the east. The principal designers of these docks were the architects and engineers Daniel Asher Alexander and John Rennie, who had done so much sterling work on the English Canal Network.

As a major inland port, situated in the heart of London, the docks were used to land and distribute high-value luxury commodities such as ivory, spices, coffee and cocoa as well as wine, wool and tobacco for which beautiful warehouses and wine cellars were constructed, alongside the wharfs.

In 1864 the London Docks were amalgamated with St Katharine Docks. Strangely the dock system was never connected to the railway network, and therefore the cargos that were handled from all around the world began their journey to the heart of the Empire by road. In common with the rest of the enclosed docks, the London Docks were taken over by the Port of London Authority in 1909.

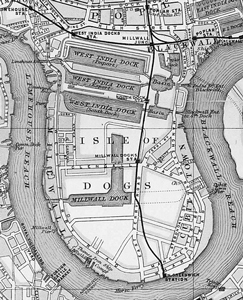

Slightly further down the River Thames are the site of the West India Docks, a collection of three docks, the Northern most of which was the Import Dock, the middle which was the Export Dock and the lower South Dock . The docks were accessed via Blackwall Reach on the Thames, with boats able to pass through the Isle of Dogs and re-join the Thames at Limehouse Reach.

The Import Dock originally comprised of 30 acres (120,000 m2) of water and was 155 metres long by 152 metres wide, whilst the slightly smaller Export Dock covered 24 acres (97,000 m2) and was 155 metres long by 123 metres wide. By having separate docks for loading and unloading, it was hoped to avoid vessels taking up valuable quay space for long periods of time. Between them, the two docks had a combined capacity to berth over 600 vessels, and locks and basins at either end of the Docks connected them back to the River Thames.

The design of the docks allowed a ship bringing cargo in from the West Indies to unload in the northern dock, sail round to the southern dock and load up with export cargo in a fraction of the time it had previously taken, given the heavily congested and dangerous upper reaches of the Thames.

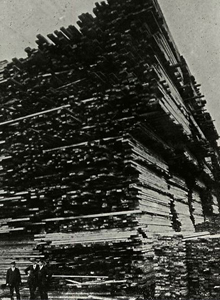

Initially the docks dealt solely with produce from the West Indies, with the exception of tobacco, and supervised the loading and unloading of vessels as decreed by Parliament. As a result, West India Docks mainly traded in rum, molasses and sugar. Imported and exported cargoes were wide ranging and included such commodities as Jute, Coir, Oil Spirits & Wine, Shell, Horn, Cork, Indigo, Spices, Baggage, Coffee and Hardwood.

During the 20th century, the docks also handled grain and, as refrigeration became common, meat, fruit and vegetables also became regular commodities.

The docks closed to commercial traffic in 1980 and the Canary Wharf development was built on the site

The costermongers had always had a tradition of organizing a whip-round for any of their number who had fallen on hard times, and Henry now asked them to help him with his charity work. They adopted the same style of costume, and as a result, the pearly monarchy and its tradition of raising money for charity began.

The costermongers had always had a tradition of organizing a whip-round for any of their number who had fallen on hard times, and Henry now asked them to help him with his charity work. They adopted the same style of costume, and as a result, the pearly monarchy and its tradition of raising money for charity began.